What’s Really Going On in South Carolina’s Measles Outbreak?

February 10 | Posted by mrossol | Critical Thinking, Experts, Health, Science, VaccineThis is the kind of inquisitive reporting needed to help us all ‘follow the science’. Key data points are missing that would allow a rational assessment. mrossol

Source: (13) What’s Really Going On in South Carolina’s Measles Outbreak?

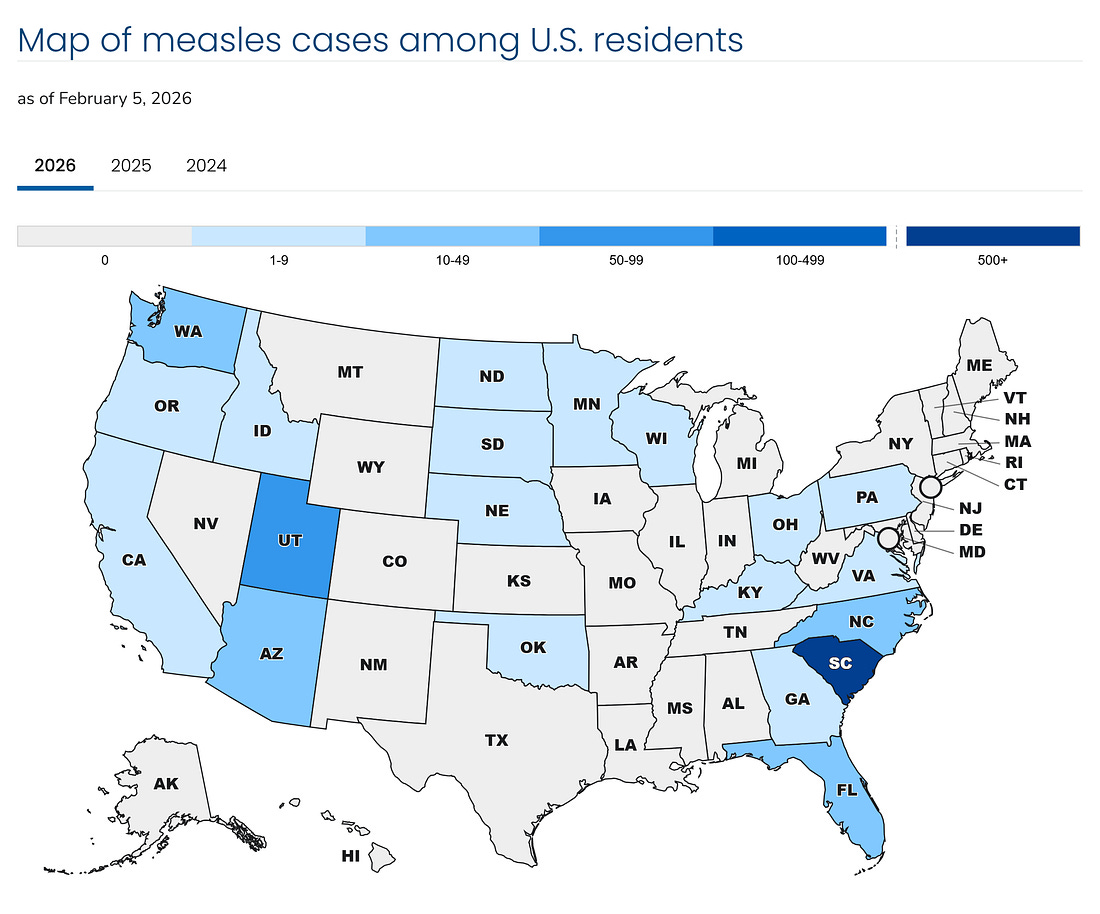

As of early February 2026, South Carolina remains the center of the largest measles outbreak in the U.S. in over 30 years. With 920 confirmed cases and over 90% reportedly occurring in “unvaccinated” individuals, headlines suggest a crisis of vaccine refusal. But beneath the headlines lies a more complex picture—one shaped by data classification, eligibility confusion, and methodological blind spots that public health authorities have failed to address.

This article unpacks the numbers behind the outbreak, highlights structural flaws in case reporting, and shows why surface-level interpretations of vaccination status are no substitute for scientific analysis.

The Breakdown: What the Public is Told

The South Carolina Department of Public Health (DPH) reports that among the 920 confirmed measles cases:

- 840 were unvaccinated

- 20 received one dose

- 24 received two doses

- 36 had unknown vaccination status

Roughly 90% of cases occurred in children under 18, with over 240 cases in children under age five. The age data are not granular enough to ascertain vaccine limitation in the very young. The narrative from DPH and echoed by national outlets is clear: this is a vaccine-preventable outbreak, driven by refusal and under-vaccination.

But this framing conceals more than it reveals. The raw case counts are not the problem—what’s missing is the structure needed to interpret them.

Source: CDC. Accessed 2/9/2024

Problem #1: “Unvaccinated” Includes the Ineligible

The term “unvaccinated” is used indiscriminately in public health summaries, but it should not be. Infants under 12 months are not eligible for routine MMR vaccination. Many children aged 6–11 months in the outbreak region were given early doses during the outbreak, which do not count toward the standard two-dose schedule and are inconsistently recorded.

Without separating:

- Infants under 6 months (not eligible for any dose),

- Infants 6–11 months (may have received early-dose, not credited toward series), in spite of no expectation of seroconversion,

- Children 12–15 months (due for routine dose 1),

…the label “unvaccinated” conflates ineligibility with refusal and erases any possibility of accurate attribution. This is more than a messaging error—it is a classification flaw that alters risk modeling and public interpretation.

DPH currently collapses all of these ages into a “0–4 years” bin, which fuses distinct immunological categories into one misleading risk cohort.

Problem #2: No Denominators, No Meaningful Vaccine Effectiveness Estimate

You cannot compute vaccine effectiveness (VE) from “percent vaccinated among cases.” VE requires known denominators—how many vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals were at risk, exposed, or susceptible during the outbreak.

VE = 1 − (Attack Rate in Vaccinated / Attack Rate in Unvaccinated)

Without population denominators stratified by age and vaccination status, especially for Spartanburg County (which accounted for 95% of cases), even the most basic estimates of attack rate are impossible.

To illustrate: even if only 2.6% of measles cases occurred in fully vaccinated individuals, if the vaccinated population was much larger and more exposed, that percentage could represent significant vaccine failure. Conversely, it could indicate strong protection. Without denominators, both interpretations are speculation.

Problem #3: Misclassification of Vaccine-Strain Rash Illness as Wild-Type Measles

The CDC acknowledges that 5–7% of individuals vaccinated with the live-attenuated measles virus develop a rash and fever post-vaccination. These are not contagious, but they can meet the clinical case definition for measles if genotype testing is not performed.

In January 2026 alone, over 1,200 infants aged 6–11 months were vaccinated in the outbreak region. If any developed rash within 21 days and were not tested using genotype assays or MeVA RT-qPCR (which detects vaccine-strain genotype A), they may have been misclassified as measles cases.

To date, DPH has published no data on how many cases were tested for genotype, or how many of the 24 “fully vaccinated” cases occurred shortly after vaccination. Without that, the actual number of vaccine-breakthrough wild-type cases may be far smaller than reported.

Problem #4: Confirmation Method Is Not Disclosed

There is no published breakdown of how each case was confirmed:

- PCR-confirmed (virologic)

- IgM-confirmed (serologic; cross-reactivity possible)

- Clinically diagnosed (symptoms only)

- Epidemiologic linkage (exposure-based, not tested)

Many measles outbreaks in high-vaccination settings rely heavily on epi-linkage. This means one PCR-confirmed case can result in dozens of secondary cases being “confirmed” by association—without additional testing.

In the absence of transparency on confirmation methods, the reliability of the full 920-case figure remains in question.

Problem #5: No Cross-Tabulation of Vaccination and Severity

DPH reports approximately 2% hospitalization rate—a strikingly low figure compared to historic measles outbreaks, which often involve 15–25% hospitalizations due to complications like pneumonia and encephalitis.

Yet DPH has released no breakdown of hospitalizations by vaccination status or age group. Were vaccinated individuals hospitalized? Were the hospitalized infants too young for vaccination? Was there clustering among the unknowns?

Without these cross-tabs, we cannot assess whether the vaccine reduces severity or whether different groups face different clinical risks. This missing data is critical.

Problem #6: Maternal Immunity Has Shifted

In past generations, infants born to mothers who had natural measles infections inherited robust maternal antibodies that lasted 12–15 months. Today, most mothers were vaccinated—not infected—and the antibody titers passed to their infants wane far earlier.

This leaves infants vulnerable during the first year of life—before eligibility for routine MMR. The outbreak pattern reflects this shift, with a disproportionate burden on infants who would historically have been protected passively.

Blaming parents for failure to vaccinate their babies under one year of age ignores the structural change in measles immunity ecology caused by vaccine-driven elimination of natural infection.

Problem #7: No Public Access to the Raw Case Data

As of February 2026, DPH has not released a de-identified case line list. A minimal scientific dataset should include:

- Age in months

- County of residence

- Rash onset date

- Confirmation method

- Vaccination status and dose dates

- Hospitalization status

- MeVA or genotype result (if any)

Without this, the public and scientific community cannot audit the basis of outbreak size, severity, or vaccination linkage. Claims made without accessible data are not scientific conclusions—they are assertions.

Problem #8: Surveillance Is Not Designed to Test the Vaccine

Disease surveillance is built to detect outbreaks, not to evaluate vaccine efficacy. Case-based surveillance counts “cases”—not population at risk, exposure time, or dose response over time.

Yet DPH and CDC messaging routinely equate “few vaccinated among cases” with “proof the vaccine works.” This is a misapplication of surveillance architecture. It leads the public to false confidence when outcomes improve—or false blame when they do not.

Problem #9: Lot Number and Cold Chain Audits Are Omitted

If the 24 “fully vaccinated” cases are true breakthrough infections, a real scientific investigation would ask:

- Were those doses clustered in time or location?

- Were they from the same vaccine lot?

- Were there cold-chain issues or administration errors?

DPH has published no such audit, despite having all vaccination records and batch numbers in state immunization registries. If these breakthrough cases represent systemic failures, the problem is logistical, not immunological. And it’s traceable.

What We Need Now

To move from press-release theater to actual outbreak science, DPH must publish the following:

- A de-identified case-level dataset (age, county, onset, confirmation, vaccine history, outcome)

- Genotype/MeVA testing data to distinguish vaccine-strain illness from wild-type

- Hospitalization data stratified by age and vaccination status

- Population denominators for each affected county by age and vaccination status

- Lot number and cold-chain data for all breakthrough cases

These are not unreasonable demands. They are standard practice for evaluating public health claims.

Conclusion

The South Carolina measles outbreak may be real. But parts of its reported size and severity may be inflated by classification error, eligibility collapse, and denominator omission.

The MMR vaccine may still be effective—but if so, that fact must be demonstrated with properly structured, auditable data. The public deserves more than simplified charts and slogans. It deserves the truth—structured, disclosed, and falsifiable.

Until that data is published, the story of this outbreak remains incomplete.

We’re watching. And we’re not done asking questions.

Thank you for being a subscriber to Popular Rationalism. For the full experience, become a paying subscriber. And check out our awesome, in-depth, live full semester courses at IPAK-EDU. Hope to see you in class!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.