The Most Important Lesson of President Biden’s Paxlovid Treatment

August 3 | Posted by mrossol | Critical Thinking, Interesting, ScienceSource: The Most Important Lesson of President Biden’s Paxlovid Treatment

It’s not what you think…

|

|

President Biden’s recent viral infection and his treatment with nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) offers the public a vital lesson in evidence-based practice.

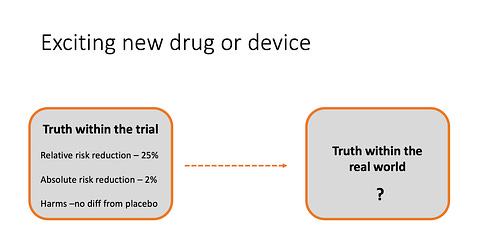

The crucial learning point involves how doctors apply results from trials to actual practice. We call this the external validity of a trial and it refers to how applicable a trial’s results are to everyday patients.

For instance, a trial may show that a drug or procedure produces benefit, but then we have to decide if the results apply to the patient in front of us.

Let’s first set out that a trial is internally valid, meaning it is well-conducted and the results are strong, statistically robust and free of bias. That’s just the starting point.

External validity is hard because trials typically enroll motivated patients who are most likely to benefit from the intervention. Trialists often exclude patients with milder forms of disease, or those who don’t have social supports, or those who have too many other diseases.

But it’s not just the fact that trials enroll ideal patients, doctors also have to consider the trial environment—which I call a best-case scenario.

In trials, ideal patients are treated by motivated clinicians who are often proponents of the treatment being tested. Trials usually have research nurses and pharmacists who oversee the treatment plan, making sure patients get follow-up and avoid drug interactions.

The Paxlovid Story

The first trial, called EPIC HR, delivered a home-run. Compared with placebo, the antiviral reduced COVID-19 related hospitalization or death by a massive 89%. All 13 deaths in the trial were in the placebo arm. The fast-thinking response would be that we need to get this drug to everyone infected with the virus.

Yet even this super-positive trial had important caveats: it enrolled unvaccinated patients with at least one high-risk feature (advanced age or high body mass index, heart disease, etc) and it was conducted during mid-2021—well before the less virulent Omicron variant was dominant.

The question now is whether the drug would produce the same effects in vaccinated patients infected with a different strain of virus.

Recent data suggests that the efficacy of the antiviral may turn on patient characteristics. The company has halted enrollment in EPIC-SR, a trial of unvaccinated lower-risk adults or vaccinated patients with at least one risk factor. In a press release, Pfizer noted that the primary endpoint of self-reported, sustained alleviation of all symptoms for four consecutive days was not met and that there was a very low rate of hospitalization or death in this standard-risk population.

The take-home: the same drug produced different results based on its use in different patients.

Biomedicine is replete with examples of this issue. Here are three in my field and one in cancer medicine.

The Internal Defibrillator (ICD)

The seminal trials showing that an internal defibrillator reduced death vs standard care, SCD-HeFT and MADIT II, enrolled mostly male ambulatory patients with preserved kidney function who were aged 60 and 64 years respectively. Do these results apply to all (or even most) patients with low ejection fraction and heart failure?

No, not likely. This substudy of SCD-HeFT found that the ICD delivered no significant benefits to those who performed poorly on a 6-minute walk—a surrogate for good health. This meta-analysis found no significant benefit to the ICD in patients with poor kidney function compared with those who had normal kidney function.

Low-risk patients may also not garner a net benefit from the ICD. This group used a risk score and applied it to patients in the MADIT II trial and found a U-shaped curve of ICD benefit. Within that “positive” trial, ICD efficacy was not different from standard care in patients with either low or high-risk scores.

Atrial Fibrillation

The CASTLE-AF trial found a huge advantage for ablation of atrial fibrillation over medical therapy in patients with heart failure who had an ICD. The 38% lower rate of death and or hospitalization for heart failure in the ablation arm was convincing.

Who were these patients that did so much better with ablation?

They were young (age 64), mostly male, non-obese, patients who were could tolerate medical therapy of heart failure. They were also pretty rare; the trial screened slightly more than 3000 patients to enroll about 400 patients. These were not like the majority of patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation that I see every day.

Heart Failure

Placebo-controlled trials have confirmed incremental benefit in four classes of drugs in patients with heart failure due to reduced heart function. Yet most patients enrolled in these trials were stable enough to come to an outpatient clinic. Some of the trials had run-in periods that allowed selection of patients who tolerated the drug.

This registry of real-world practice found that only 1% of patients were taking maximal doses of all four classes of drugs.

Some heart failure experts lament the fact that uptake of these drugs remains poor.

One reason for low uptake is that doctors are dumb or lazy.

The more likely reason is that heart failure trials are designed to show if a treatment works. And to do this, you select patients that are most likely to benefit, and you provide careful follow-up within the confines of a trial.

This sort of care is not representative of the real world. Consider that just the matter of switching doses of drugs is difficult without research nurses or pharmacists.

Cancer Medicine

Academic cancer doctor Bishal Gyawali has written often about the problem of interpreting evidence derived from ideal patients in chemotherapy trials. He sent me the example of a drug for liver cancer called sorafenib, which was shown beneficial in a clinical trial published in 2008.

Since liver cancer has such a poor outlook, you’d expect an effective drug to reduce deaths. Yet death due to liver cancer actually increased between 2011-2015. Why would this be?

One reason could be that the original trial enrolled ideal patients that were less sick than the typical patient with liver cancer.

Indeed, using an observational database, this group found that survival in the placebo group of the original trial was better than survival in real-world patients treated with the drug. Pause there and re-read that sentence.

None of these examples are nefarious. I don’t doubt the results of any of these trials. In the populations studied, at that time, in that environment, the benefits were as reported.

The challenge is how to use evidence taken in the special circumstance of a trial to people in the real world.

I have often said that use of evidence is what separates doctors from palm readers. The discovery of the randomized controlled trial may be one of the greatest medical inventions of all time. I love evidence!

Yet the use of this evidence can never be as algorithmic as guidelines or quality measures or news stories make it seem.

The high-profile nature of the American president taking a medicine that worked in one set of criteria but might not work in his specific scenario provides everyone an opportunity to appreciate the complexity and uncertainty of translating trial results to the patient before us.

This is one of the hardest jobs of the modern clinician—and to me that is a good thing. For it were easy, we could be replaced by robots.

If you liked this post from Sensible Medicine, why not share it?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.