A Flawed Analysis: More Distrust of Public Medicine

February 20 | Posted by mrossol | Health, Incentives, PharmaSource: A Flawed Analysis Induces Severe Sadness

What follows is one of the hardest columns I have written in a long time. Such an appraisal could never appear in a journal. It could not be written by a young person hoping to move up in academia. This is the value of Sensible Medicine. We aim to stay user-supported so that flawed papers can have proper criticism.

I mean no malice to the authors. My debate is with their methods and their words.

I am sorry to say that there is more bad news regarding the state of medical evidence. No, not in COVID-19 science, but in my field of cardiology.

I want first to say how sad this story makes me. Sad because it involves a journal that once had a reputation for accepting strong papers. Sad because many of the authors have had or are destined for leadership positions. And sad because the biased results will be used as marketing propaganda to convince patients to have an unproven procedure.

The journal Circulation published a comparison study of older patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who were treated with either standard anticoagulant drugs or procedure called left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO).

Some brief background: both of these treatments are stroke prevention strategies. Anticoagulant drugs have proven effective in trials that enrolled tens of thousands of patients. Devices that occlude the left atrial appendage barely passed FDA muster in much smaller trials. I’ve summarized the case against appendage occlusion with devices in this video.

I (and most of my colleagues) think that anticoagulant drugs are the better strategy for most patients. We think that because the appendage device did not reduce stroke or major bleeding in the seminal trials against warfarin. But now we use better anticoagulants than warfarin.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that you thought there was uncertainty regarding which strategy (drugs or device) best protected patients with AF from stroke. There would be only one way to find an answer: you randomize patients to either of the two strategies and then count up strokes.

But that is not what the authors did.

Instead, they used a Medicare claims database to find patients treating with each of these two procedures. They then used statistical adjustments in an attempt to match patients.

Of course, simulation of randomization is impossible in this case because a clinician chose to use either of the two treatments. That clinician used many factors to decide. Some of these factors go on a spread sheet and can be used for adjustment; some factors don’t make it on a spreadsheet.

The beauty of randomization is that it balances both types of factors—known and unknown. Then you can make a (mostly) unbiased comparison of outcomes and infer causality.

The authors reported that left atrial appendage occlusion was associated with a near 50% reduction in death at one year. The device was also associated with a 34% reduction in stroke and overall little difference in major bleeding.

The main graph from the study is shown below. You can see that the survival curves start separating in months. I’ve added the red box and a caption:

The authors conclude: (Read the italicized second sentence slowly.)

In a real-world population of older Medicare beneficiaries with AF, compared with anticoagulation, LAAO was associated with a reduction in the risk of death, stroke, and long-term bleeding among women and men. These findings should be incorporated into shared decision-making with patients considering strategies for reduction in AF-related stroke.

Comments:

I hope you are shocked.

There is no way that a plug in the appendage could lead to lower death rates within months. The fact that the curves separate this early is near proof of bias.

I realize many readers are not content experts so let me offer three lines of evidence why this is biased and two reasons why the authors obtained this result. (Then we need to move on to the authors conclusions and what this paper says about the state of medical science.)

Three Reasons LAAO Does Not Reduce Mortality

— Occlusion of the left atrial appendage is a stroke prevention strategy. Stroke is a very uncommon cause of death. Even if the device actually reduced stroke due to clots (ischemic), it would take years and years to reduce death.

— Canadian investigators have published an actual randomized trial, called LAAOS-III, in which they showed that surgical appendage closure (vs no closure) at the time of heart surgery reduced stroke by a statistically significant 33%. This remarkably positive result in stroke reduction was not enough to change death rates over 4 years.

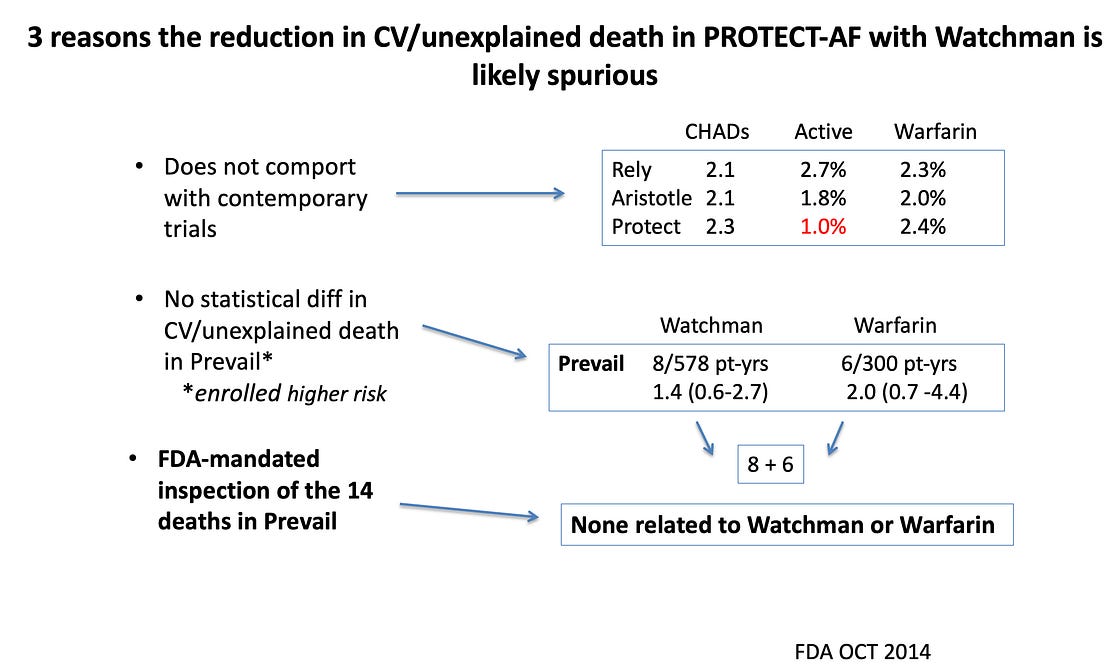

— In the seminal trials of appendage closure vs warfarin, the first trial (PROTECT AF) reported a striking reduction in death due to cardiovascular causes in the device arm. FDA seemed surprised by that and in the second trial (PREVAIL), they mandated inspection of all deaths that occurred in that second trial. They found that none of the deaths were related to either the device or anticoagulation. IOW: it was all noise. See slide:

Two Reasons For These Biased Results

The first reason the survival curves separate so early is that doctors chose to close appendages in healthier patients. This is a form of selection bias, which cannot be adjusted for in non-random comparisons.

The second reason is something called immortal time bias. From the catalog of bias:

‘Immortal time’ is when participants of a cohort study cannot experience the outcome during some period of follow-up time.

What About the Conclusions?

These findings should be incorporated into shared decision-making with patients considering strategies for reduction in AF-related stroke.

Pause there and think what this means.

Leaders in the field do not propose that these non-random retrospective observations be used to generate hypotheses for future trials. They want us to use this data in discussions with patients. The number of patients who would not select a procedure that reduced their chance of dying in the first months is exactly zero.

But, as I have shown, this is surely a biased result.

The next logical steps are scary. Pause again.

Either these medical leaders want us to use flawed data to convince patients to have an unproven procedure or they don’t know the data is biased.

I am not sure which is worse. I offer this picture without comment.

The State of Medical Science

One wonders why the authors thought such a study was worth doing. They surely know that an appendage occlusion device cannot reduce mortality in one year—or even many years.

Where was peer review? Where were the editors of Circulation?

If such a paper can pass peer review at a prominent journal, how can a consumer of medical evidence have confidence in the adjudication of any paper? The implications are devastating.

The Fight Against Cynicism

I, and likely you too, fight the urge to be cynical about medical evidence. We hope upon hope that things will improve. We lean on academics and journals to rise above the temptation to publish papers like this. Or at least not to conclude that we should use such data in patient discussions.

But when we see a flawed mortality curve credulously tweeted out, and we know that it will soon be part of a company’s marketing program, how are we supposed to keep cynicism at bay?

Tell me, please. Help me not go there. I keep an open and optimistic mind.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.