What it Takes to Actually Achieve Shared Decision Making.

January 9 | Posted by mrossol | Health, Math/Statistics, MedicineA bit of push back, or maybe just elaboration, on a recent post.

By James McCormack, Jan. 8, 2024. Source: What it Takes to Actually Achieve Shared Decision Making.

James McCormack has written on Sensible Medicine in the past. He is a Doctor of Pharmacy in the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of British Columbia. Last month he reached out to me to let me know he thought I gave short shrift to a discussion of shared decision-making in one of my articles. Not only was his email a particularly kind and Canadian one, but he was also completely correct. James generously accepted my invitation to expand his email into this post.

I knew we had to publish when I reached the part when he writes, “Too many times I have heard patients say they have “suffered” for years with their cholesterol or diabetes or blood pressure. These conditions are almost always asymptomatic. It is difficult to make an asymptomatic patient feel better. Thus, what patients must be describing are the negative impacts that surround the treatment and monitoring of these conditions.

This piece is a bit longer than our usual, but I think it is worth the time.

Adam Cifu

In his December 1 article, “Disagreement and Chagrin in Therapeutic Decision Making” Adam Cifu described his approach for how he might “convince someone with a 10-year cardiac risk of 13% to begin a statin for primary prevention.” He then added that he would “engage in a conversation that sounds like this.” He then went on to describe what that conversation might sound like.

As I read his approach to the statin scenario, there were some points where I felt the discussion needed more elaboration, evidence, and a specific focus on getting to the point of a shared decision.

First, I believe in most cases it is not our job to “convince” someone to take a medication like a statin. If you believe this is your job, then shared-decision making will often be an almost obstructionist concept. Glyn Elwyn and I wrote in a 2018 paper “in the vast majority of circumstances, the only outcome of relevance for EBP (evidence-based practice) is to measure whether a shared decision was made.” It is not our job to convince patients to do something but rather to convince them, where possible, that before a decision is made, they need to appreciate and understand the risks, benefits and harms of what is being proposed. In other words, replace your enthusiasm for treating, with an enthusiasm towards getting the patient to understand the information well enough to make a shared decision.

Adam’s description of his theoretical conversation began as follows.

ADAM TO HIS PATIENT:

Because your risk of experiencing a cardiovascular event (heart attack, stroke, new angina, sudden cardiac death) over the next 10 years is 13%…”

To have the focus be on important cardiovascular (CV) outcomes and not on surrogate markers is a great start. For decades, the medical profession has taught people to know and fear their “numbers.” Unfortunately referring to blood pressure and lab tests, rather than the number that really matters – their risk of a bad health outcome. Too many times I have heard patients say they have “suffered” for years with their cholesterol or diabetes or blood pressure. These conditions are almost always asymptomatic. It is difficult to make an asymptomatic patient feel better. Thus, what patients must be describing are the negative impacts that surround the treatment and monitoring of these conditions. Refocusing the issue away from surrogate markers and onto important clinical endpoints is a key first step if shared decision-making is truly the goal.

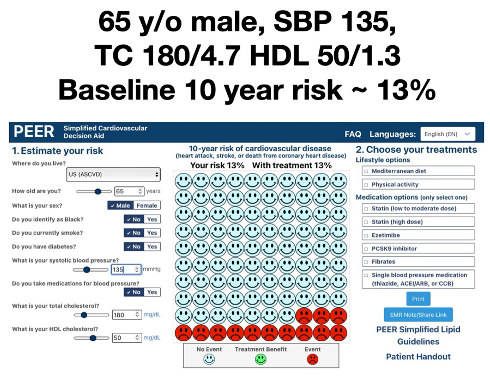

In Adam’s scenario, it’s likely the patient’s 13% risk came from a cardiovascular (CV) risk calculator tool. To facilitate this discussion, I used the ASCVD calculator to create a fictional patient who would have a 13% 10-year risk of a CV event (a fatal or non-fatal heart attack or stroke). The patient is a non-diabetic, 65 y/o male, SBP 135, total cholesterol 180 mg/dL (4.7mmoles/L) and HDL 50 (1.3). The risk tool I used is part of what our group developed in the just released revision of our national Simplified Lipid Guidelines for Primary Care. The Simplified Cardiovascular Decision Aid can be found here.

ADAM CONTINUED:

…you would benefit from a cholesterol lowering statin medication” I would start 10 mg of atorvastatin daily. What do you think?

Adam is technically correct – there is a possibility this person could benefit from a statin – however I would bet if we were to tell a patient they “would benefit from a statin” their expectations of the benefit would be much higher than what the best available evidence reveals. For example, when patients after a heart attack were surveyed about what they believed would be their chance of benefitting from their preventative medications over the next 5 years, the median response was 70%. However, in reality their absolute benefit over 5 years is actually <10%. Interestingly, only 4% of people surveyed estimated correctly that their benefit would be <10%.

It is important to appreciate that patients are likely coming in with a greatly exaggerated belief about the benefits of our preventative treatments. This is especially important when it comes to primary prevention discussions because even the 10-year absolute benefit is likely closer to 2 to 6% – a number which is clearly orders of magnitude lower than their preconceived notions. So, when it comes to preventative treatments, our very first job very much needs to be educational as this may be the first time a person has discussed their CV risk and/or heard of a statin. An essential part of shared decision-making is to help educate the person about their risks, benefits and harms in an understandable way a with the proper contextual framework. The following are some ideas and approaches you may find useful.

RISK FACTORS AND CV RISK NUMBERS

1) Explain why we measure risk factors/surrogate markers like blood pressure, lipids and glucose

A key starting message to get across is for the patient to appreciate the reason why we measure surrogate markers in the first place. These risk markers have been shown, in most cases, to be associated with an increased risk of CV events and the point of measuring them is simply to help us make a more informed estimate of their risk of CV outcomes. Rarely should elevated blood pressure/lipids/glucose be considered a “disease”. They are simply risk markers. Unfortunately the media, marketing and sometimes clinicians will refer to hypertension and diabetes as the “silent killers” or suggest that cholesterol “plugs your arteries” – phrases that suggest a much more ominous risk than is likely warranted. I would even add it is not a great idea to say your numbers are “good” or “bad” or “normal.” Using these sorts of indefinite numeral adjectives to describe risk is almost guaranteed to result in a misleading interpretation.

2) Describe what it means to have a heart attack or a stroke

Many people don’t have a clear understanding of exactly what a heart attack or a stroke is and/or their consequences (consider how many heart attacks in popular TV shows and movies are portrayed as a fist clenched to the chest followed immediately by cardiac arrest). It is sometimes useful to ask them to explain what they think these health issues entail first and go from there. Without knowing what to expect it is hard to make an informed decision. Find out what they think/know.

3) Put the estimated CV risk percentage into a proper context

First off, I explain all we can do is give a ballpark estimate. Despite the fact a risk calculator will typically give what seems to be an exact specific percentage risk – 13% in our scenario – these estimates carry a reasonable amount of uncertainty. In the risk range of 10-20%, the uncertainty is, at best, +/- 2-3%. Once risk gets over 20%, the uncertainty is +/- 5-10%. For our scenario I would simply say the best estimate of your 10-year risk is likely somewhere between 10-15%. Now I have found percentages can be confusing to some people, so typically I would add in that 10-15% means somewhere between 10-15 people out of 100 like you will experience a CV event over the next 10 years. In addition, using a visual representation to display the risk is also likely to help the patient appreciate their risk. Our decision aid provides all this on one page.

4) Put the impact of each risk factor into context

One of the key messages to alleviate the misinformation and fear around CV risk factors is to show that almost always the biggest risk factor is age (and then sex, if the person is male). Obviously, there is nothing we can do about those 2 risk factors.

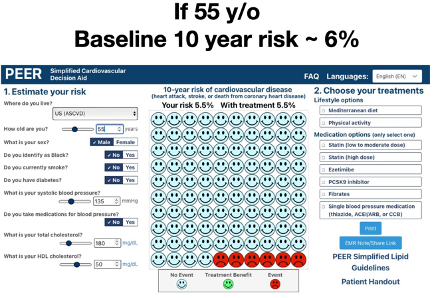

The impact of age on 10-year cardiovascular risk

To do this I will often change the age in our decision aid and show what this does to the 10-year risk. The examples below show the impact of simply changing age on 10-year risk for our scenario – keeping all the other risk factors constant.

The 10-year CV risk would be

~2% at age 45

~6% at age 55

~13% at 65 (their risk today)

~25% at 75

So in this scenario, risk roughly doubles every 10 years simply because of age.

The impact of blood pressure on 10-year cardiovascular risk

To put surrogate marker numbers into context it is essential we show patients what happens to their CV risk if their baseline blood pressure was somewhat higher or lower. In this case, if their systolic blood pressure had been 125mmHg and not 135mmHg their baseline risk would be 2% lower over 10 years – 13% vs 11%. If their systolic blood pressure had been 145 instead of 135, their baseline risk would be 2% higher over 10 years – 13% vs 15%.

So, a 20mmHg difference (from 125 to 145) only changes the 10-year risk estimate by ~4%. In my experience people are surprised by how little the risk changes with fairly big blood pressure differences.

The impact of lipids on 10-year cardiovascular risk

Then, do the same for total cholesterol. If their total cholesterol had been 135mg/dL (3.5mmoles/L) not 180, their baseline risk would be 2% lower over 10 years – 13% vs 11%. If their total cholesterol had been 225 (5.8) not 180, their baseline risk would be 2% higher over 10 years – 13% vs 15%. So very similar with what was seen with a 20mmHg difference in systolic blood pressure.

THE IMPACT OF LIFESTYLE CHANGES AND DRUG TREATMENTS ON CV RISK NUMBERS

Once the patient has an appreciation for their 10-year CV risk, the next discussion should be around what the best available evidence suggests might happen to risk if certain lifestyle changes or drug treatments where instituted. This can easily be shown for interventions such as the adoption of a Mediterranean diet or an increase in physical activity. The evidence from 3 RCTs suggests the Mediterranean diet reduces risk relatively by ~30%. Based on that evidence, in our scenario, clicking on a Mediterranean diet shows the impact of this diet on the person’s 10-year CV risk would be to reduce the risk estimate from ~13% down to ~9% – a benefit at least as good as taking a statin, and much tastier. Interestingly this is despite the fact that the Mediterranean diet has little if any impact on surrogate markers. One of the best things about a Mediterranean-style diet is it focuses on the quality of the diet rather than focusing one a single nutrient or food group. In addition, it doesn’t ban entire food groups making it fairly simple to follow long-term. An example of a typical Mediterranean diet can be found here.

Physical activity also likely has an impact on CV risk with the best available evidence (although from observational studies) suggesting an ~25% relative benefit. In our scenario clicking on physical activity shows that 10-year CV risk would be reduced risk from ~13% down to ~10%. An activity prescription may be a useful tool to provide more concrete guidance for patients.

MEDICATIONS

Statins

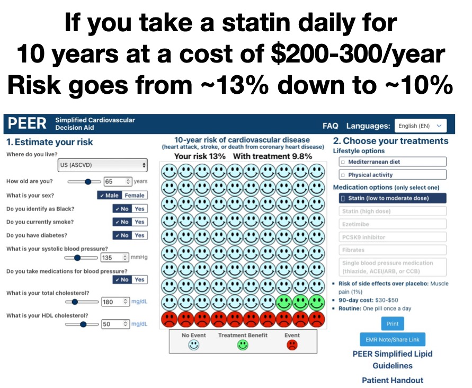

Statins are by far and away the medications most often used to reduce CV risk and they have also been studied more than almost any other class of medication. There is ongoing debate as to how they work, but that debate is really not that important. Rather the issue really is simply, do they work and if so, how big is the effect? Statins have consistently been shown to reduce the relative risk of CV outcomes by ~25% when compared to placebo – a benefit that is roughly similar to what is seen individually with the Mediterranean diet and physical activity. In this case, the patient can be shown a statin taken daily will reduce their 10-yr risk of CV outcomes from ~13% down to ~10% or a 3% absolute benefit.

Providing these numbers alone may be enough, but I will often add in that this 3% difference means that 3% of people benefit and 97% don’t – or roughly 1 in 33 people will get a benefit from taking a statin for 10 years.

THE SIDE EFFECTS OF MEDICATIONS

THE PATIENT TO ADAM:

Don’t the medications have side effects?

There is value to first setting the stage around potential side effects. All medications have the potential to cause side effects. I always say a drug without a side effect is a drug without an effect.

Statins

Rick of side effects over placebo: Muscle pain (1%)

90-day cost: $30-$50

Routine: One pill once a day

Statins have been studied in millions of people and the best evidence suggests the one side effect that might be caused by statins is muscle soreness. Statin-induced muscle soreness occurs in ≤1% of people over placebo. However, in clinical practice, roughly 10% or 10 out 100 will complain of muscle aches, but interestingly, the best available evidence suggests that for no more than 1 out of these 10 is it really the statins contributing to the muscle aches. Nonetheless, it’s worth saying to a patient if you do develop muscle aches that don’t seem to go away you need to let me know so we can possibly reduce the dose or switch to a different agent. Saying this to patients upfront can help assuage them that there is a backup plan in place if things don’t go as planned and that their concerns will be heard.

When it comes to blood pressure medication roughly 10% will stop due to side effects (they vary depending on the class of agent) – but that means 90% don’t.

ADAM TO THE PATIENT:

They are generally very well-tolerated medications, and given your cardiovascular risk, the benefits greatly outweigh the harms.

I pretty much agree with the sentiment that statins are “well-tolerated” but what does that really mean? Saying something is “well-tolerated” is also not a truly informative way to describing potential harms. There is good evidence that describing side effects with words such as common, uncommon or rare leads to important misinformation.

These indefinite numeral adjectives have sometimes been given specific numeric ranges by drug regulators

Very common = >10%

Common = 1-10%

Uncommon = between 1/100 and 1/1,000

Rare = between 1/1,000 and 1/10,000

Very rare = <1/10,000

Now personally I wouldn’t consider a 1% chance of something happening as common. When people have been surveyed and asked what they think common means, their mean response to common is 45%. Their mean response to the term rare is 8%. In other words when we only use words to describe the risk of side effects the patient is thinking the risk of harm is far greater than the actual risk.

Importantly we will never be able to figure out if an individual patient actually benefitted from a 1-3% reduction in CV events, however we can figure out if they tolerate the medication. One approach is to offer an experiment to the patient. If a patient thinks the size of CV risk and potential benefit is large enough to possibly consider a medication a useful approach may be to try the experiment of a low dose (especially for blood pressure medications) and see how they tolerate the medication. If they experience side effects then likely that specific medication is wrong for them, but if they don’t then the harm from side effects for that particular patient become 0%, other than the inevitable cost and inconvenience.

THE PATIENT TO ADAM:

I don’t think I want to take it.

ADAM TO THE PATIENT:

OK.

I believe before a decision is made there may be value to printing out/sending a link to all this information https://decisionaid.ca/cvd/ so that a patient can think about all this “new” information outside of the office environment. There is likely value in talking to family and friends for some people. Often a patient will ask, “well what would you do”. If that question is asked you can respond by either saying it doesn’t really matter what I would do as it will be you taking the medication, however if you really want to know, this is what I would do. And then be honest about what you would do. Finally, adding the comment that “there is no urgency to treat you so you can take your time with the decision and whatever decision you make I am fine with that” is important context. The decision to treat blood pressure, lipids, and glucose can be made over weeks to months.

A REALITY CHECK

Clearly the above information and ideas can’t all be done in a 10-minute visit. However, the decision to begin a medication, one that a patient might continue for decades, should not be taken lightly and in primary prevention there should never be a hurry. Our job as clinicians is to help patients make an informed decision. Fortunately, when it comes to cases such as the one presented, we have tools and evidence to help with the decision-making process. We need to stop saying your cholesterol is high or your blood pressure is high, and it needs to be treated.

Do you need to do every part of this for every patient – of course not – simply offer some follow-up visits and maybe choose a couple of the ideas you feel are most valuable and use them with the next discussion. You will develop your own style with regards to this approach but at least you now know the information is readily available and possibly I’ve provided some useful ideas for how to put all the evidence and issues into context.

I can almost guarantee you will find this approach much more rewarding – and so will your patients.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Sensible Medicine. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.