From modular to moral: why longitudinal clinical experiences matter in professional identity formation (Part 2)

March 21 | Posted by mrossol | Critical Thinking, Medicine, ProcessIn Part 2 of Dr. Rohlfsen’s post, he goes from threats to professional identity to an exploration of the role of medical educators.

In the last post (Part 1), I discussed threats to our professional identity including “collective in-competence,” runaway “interconnectivity,” and mistrust within the educational alliance. In this post, I’ll focus on the nexus of our evolving identity with the medical education system and explore what our role can and should be as educators in forging a path forward. If we care at all about the public trust of doctors, we should pay close attention to physician identity and push to preserve it.

The analogy of a hospital’s physical expansion into an interconnected metropolis of care is an apt metaphor for the clinical learning environment not just because this is where education and identity formation occur(s) but also because it describes how systems of care (and learning) are more often retrofitted for use than intelligently designed. Even the best laid architectural plans will require massive reconstruction as the needs of a hospital system evolve. It turns out medical curricula is no different.

The unsavory truth of modern medical education is that the knowledge and skills we teach today will most likely be outdated by the time a trainee graduates. We have long crossed the rubicon of being able to “know, learn, and teach everything.” As a result, “just in time” learning, critical thinking, and problem solving matter more than an isolated score on a high stakes exam. While much innovation has occurred to ensure key information and competencies are not missed, the reality is new drugs, medical discoveries, and standards of care will henceforth be subject to “lumping and splitting” within an already oversaturated curriculum. Vertical integration of modular content may help align educational outcomes, but the vast majority of clinical education remains organized into traditional “blocks” of isolated experiences. Most concerning, few trainees enjoy the benefits of longitudinal clinical mentorship.

Is it any wonder that direct patient care feels overwhelming?

What’s the solution?

When I was a fourth year medical student, I had a once weekly continuity clinic and was given a pager for the entire year. The most formative experience of this longitudinal preceptorship was when my attending (and mentor) paged me at 6pm on a Friday to ask how I wanted to manage an acute DVT that resulted on an outpatient duplex ultrasound late that afternoon. When my response was “I’ll call ‘em to head to the ER,” I’ll never forget his response as it still echoes today, “what can we do to help?”

Keep in mind, I was useless in this situation. I couldn’t sign orders, I didn’t know which pharmacies were open, and I certainly didn’t know how to dose subcutaneous lovenox (this was back when “direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)” were still called “novel oral anticoagulants” (NOACs). To this day, I’ve thought about the value of this learning experience from multiple perspectives (e.g. distal DVT management, systems-based practice, dosing of high risk meds) but what stands out the most was the reality that a loud pager could interrupt my life in the service of a patient and I could develop both my clinical and moral sense to manage their acute concern. The patient avoided an inappropriate visit to the ER and I learned a heck of a lot about my role in medicine:

Lesson #1: when patients truly need our help, it’s rarely convenient.

Lesson #2: The best way to navigate the competing demands of medicine with any moral clarity is to develop this character in training under the direction of a trusted mentor.

Curricular design: from modular to moral

The reason our professional identities are special is not because we’re exceptionally smart, kind, empathetic, skilled, or adept at communication; it’s because we develop the strength of character to recognize when the sacrifices we make for a patient should trump all else.

While we may define the nuances of our professional identities differently (not everyone needs to be “married to medicine”), the way we learn to calibrate our altruistic actions in a sustainable manner that aligns with our values is by having tough experiences and mentorship. Looking back, what mattered in this moment was that my mentor paged me. It would have been much easier for him to manage it on his own without me pending orders from my apartment. But he went out of his way to model what characterlooks like in medicine.

Most importantly, not once did I think, “why is he putting me through this?” Because we had worked together for more than a month and he was investing in me in other ways, there was an educational alliance and trust – something that seems to be lacking these days. Even now that I’m a junior faculty member, he has permission to say things to me that I don’t like. These “desirable difficulties” make us who we are in medicine, so we need to find a way to foster (rather than avoid) them.

Within the microcosm of medicine, reverberating themes of burnout, exploitation, suicide, and patient safety can quickly raise the temperature past the boiling point. These wicked problems often hit too close to home, leaving little space for nuanced or productive dialogue, particularly within the context of our rigid and hierarchical training cultures. Mentorship just happens to transcend these tensions.

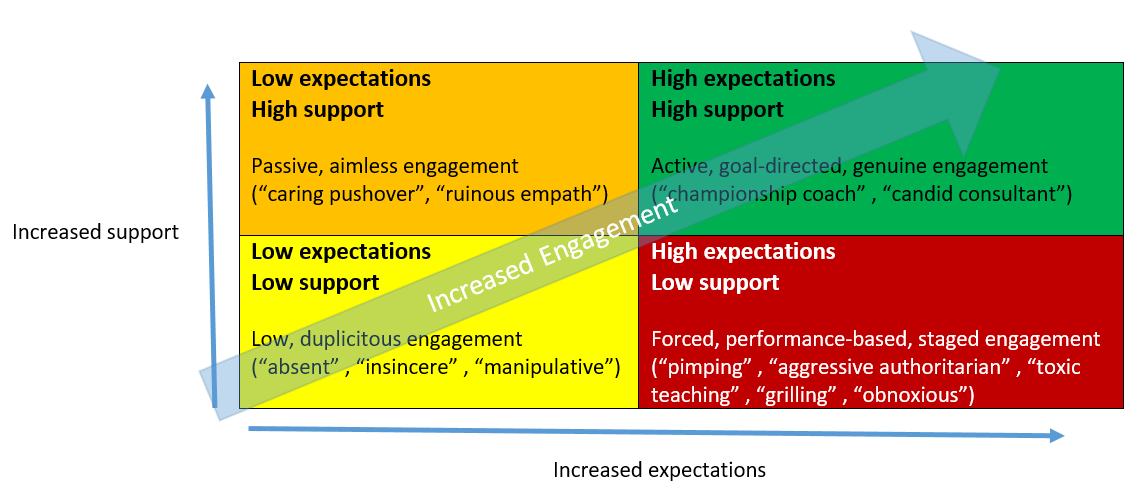

Longitudinal mentorship according to Daloz’s model (Figure below) allows high expectations and high caring to not be at odds. That said, the higher the expectations, the higher the mandate for support. Modular curricula may be able to allow for integration and assessment of new content, but it cannot teach moral judgement or character. It also cannot tailor precise learning experiences to maximize learner impact.

Because character is elusive, difficult to measure, and castigated as “hokey” in some contexts, it often gets relegated (and conflated) with being “a good person.” Unfortunately, being “compassionate” or “moral” is only a pre-requisite for good character. In other words, it’s not only necessary to recruit medical students with high integrity, conscientiousness, and altruism, it’s also necessary to develop their character in the situations that will test it throughout their careers. At the end of the day, competency is not just about knowledge or skill; it’s about attitudes and behaviors. And the integration of all of these into “wise action” or “doctoring” ultimately comes down to character. This is why I feel strongly that professional identity be at the forefront of our medical education discourse. The alternative is simply unacceptable.

A Cautionary Tale to Inform our Future Identity

Hahnemann hospital closed in 2019 leaving more than 550 residents and fellows without a home. Hindsight may be 20/20 but the sudden collapse of this Philadelphia teaching hospital could have been predicted by a long series of mismanagement decisions. Graduate medical education (GME) leaders were routinely asked by hospital owners to “right size” programs to maximize profits while desperately needed renovations to the failing infrastructure were routinely ignored. Year after year, the insidious erosion of the building led to sale of the teaching hospital to a private equity firm who within 18 months declared bankruptcy. Most nauseating, this same firm ultimately tried to “auction off” trainee spots for profit until the courts stepped in. While the focus of annual budgets distracted the more well intentioned parties, GME nearly dissolved into a market commodity – not unlike the beds, CT scans, and MRI machines that were sold to debtors. This is what happens when medical education waits and reacts to the forces around it. The original ward (a sacred and hollow place) becomes so enveloped by expanding interests that it becomes a fragmented and forgotten relic of its former self.

As AI emerges in medicine, few can predict what our future identity will look like amidst a Cambrian-like explosion event of innovative applications. We do know this – the physician identity will be in flux like never before. My guess is we’ll serve less as cognitive or procedural specialists and more as moral specialists. As this occurs, our ability to pass on the physician identity will hinge less on the sum of our knowledge and skills and more on the nature of our attitudes, values, and character. Without a strong educational alliance rooted in longitudinal, relationship-based clinical care, the wayward winds of change risk us losing our true north – an identity that wisely puts patients first.

The Real Slippery Slope

At some point, the real “slippery slope” suggested by the NEJM NOS podcast is not a generation that fails to accept the baton of patient care but rather a generation that fails to see how tenuous this handoff really is (I’m talking to medical educators). Retrofitting a construct works for a time but eventually it leads to unanticipated, disastrous consequences. We need leaders that have the moral courage to explore where we’ve failed to hold up our end of the educational bargain while also inspiring future generations about what it means to be a doctor. As this identity evolves, we also have to have the strength of character to invest in sustainable models of care. At the same time, we have to teach and mentor learners about how to recognize times when “going above and beyond” for a patient is the “right” thing to do.

At the core of what we do, this profession is special because there’s a vulnerable life at stake. Even amongst the monotony of pages, perfect serve messages, or routine clinical decisions, our actions have real impact on a human life and we should never take that for granted.

In summary, this conflict (while loaded) arose less because of a tension of generational differences and more because of a problem of misaligned incentives. Medical education (as a system) is partly to blame and it can be remedied by re-investment in clinician educators who are passionate about relationship-based longitudinal care and mentorship. Let’s do less finger pointing at well intentioned individuals and foster more dialogue towards co-construction of health systems and educational solutions that move medicine forward without leaving individuals behind.

Whether the handoff is as small as “end of shift” or as big as “professional identity,” let’s keep in mind that two parties are required to pass a baton without dropping it.

Cory J Rohlfsen is a hybrid internist, core faculty member at UNMC, and the inaugural director of Health Educators and Academic Leaders which focuses on competency-based approaches to developing future leaders, scholars, and change agents in health professions education.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.