Inside the American Redoubt

November 19 | Posted by mrossol | American Thought, Christianity, Inflation, Philosophy, Tea Party, Western CivilizationSource: Inside the American Redoubt – UnHerd

By Jacob Furred, Nov. 18, 2023

North Idaho has long been home to those seeking to escape the looming collapse of America. This is a region doused in frontier spirit; a land where people openly carry guns, and where bounty hunters still operate, tracking down fugitives hoping to bolt into Canada. It is here, on rugged fringes stalked by mountain lions, bears and wolves, that the American Redoubt was born.

The Redoubt is both a prophecy and a movement: a pre-emptive response to the anarchy on the horizon. Economic meltdown, nuclear war, the lawlessness that will follow the total defunding of the police — all, its followers warn, could bring an end to American civilisation. And so they have started to prepare. First, by relocating to easily defensible ranches in the wilderness; and second, by stocking up on food, firearms and fuel. While their country teeters on the brink of bedlam, they are building a fortress.

If the Redoubt has a Messiah, it is James Wesley, Rawles. (The comma is an affectation.) A former US Army intelligence officer, Rawles has spent decades preaching about America’s imminent implosion to thousands of Christian conservatives, and the importance of them retreating to the mountains. They first flocked to him in 1998, after his book Patriots, both a survivalist manifesto and a novel about the country’s descent into disorder, became a surprise bestseller. The Daily Beast called it “the most dangerous novel in America”; others claimed it “could one day mean the difference between life and death”. Such hyperbole only widened his appeal.

Every Redoubter has read Rawles — yet few have ever seen him in person. He disguises himself when he needs to emerge from his secret ranch to get supplies. Otherwise, he communicates through his blog to 320,000 readers a week. It’s a peculiar assortment of survivalist tips and Christian precepts: recent posts consider the benefits of stun guns, the southern border crisis, and a recipe for potato soup.

It was in 2011 that Rawles issued his definitive call to arms, informing his readers that America’s death spiral had reached its climax. Following a news report about a couple in Florida who were unable to pay for a road toll using cash, he decided the time had come for “good men to take action”— to “move to the mountains” and join the Redoubt.

Rawles’s inspiration was the Schweizer Reduit of the late-19th century, when the Swiss Government, faced with the increasing likelihood of a German invasion, proposed the construction of Alpine fortifications from where its army could make a final stand. This time, however, as Rawles explained in a clarion essay, the threats were far more profound. For decades, he wrote, secular capitalism had defiled the Christian-conservative values on which America had been built. Just as in Europe before the First World War, the forces of modernity could no longer be tamed. Instead, civilisation had become a “thin veneer”. The centre was not holding, and the United States of America was degenerating into a state of nature.

If it sounded like a programme for religious separatism, that’s because it was: “I am a separatist, but on religious lines, not racial ones,” Rawles wrote. The reason for his Christian criteria was as much pragmatic as it was theological: “In calamitous times, with a few exceptions, it will only be the God-fearing who will continue to be law-abiding.”

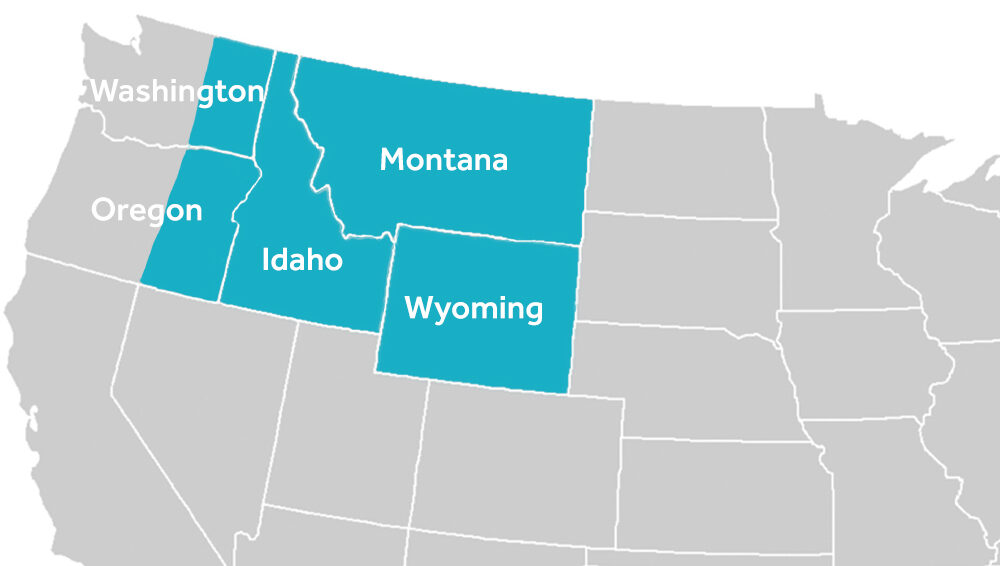

With low-density populations and abundant hydro-electric power, Rawles decided Idaho, Montana and the eastern sectors of Oregon and Washington were the perfect places to retreat. Neighbouring North and South Dakota, he explained, would not be as easy to defend: their vast plains and steppes would provide ample room for large armies to manoeuvre.

Once the call went out, the great migration started. Dedicated estates agents sprung up, offering to find plots of land or existing ranches that are sufficiently remote and easy to defend. One claims to help 3,000 fleeing Americans each year. “We do not service liberals,” boasts another. By 2015, an estimated 10,000 people had moved to the area.

And yet, as far as “community” goes, the Redoubt is a limited one. There is no official membership, and residents often live miles from civilisation. For Rawles, a “constitutionalist libertarian”, this is intentional: he sees Redoubters as neither sheep nor predatory wolves, but sheepdogs who think independently and protect their family when necessary.

But in recent years, this lack of organisational structure has allowed more inflammatory characters to gain prominence. Today, one of the Redoubt’s most notorious supporters is Matt Shea, a disgraced former Washington lawmaker who has distributed a manifesto for biblical warfare that proposed killing all males who “do not yield”. There is also John Jacob Schmidt, the host of Radio Free Redoubt, who recently warned that the rest of the country is “lucky we’re peaceful”.

Yet the wider Redoubter population can seem similarly aggressive as they police local councils and schools, making sure they don’t overstep their federal remits. Redoubt News offers a flavour of their bêtes noirs: “woke violence”, Big Pharma and government tyranny. Viewed as an offensive, rather than a defensive structure, it’s not hard to see why the Redoubt, and the man behind it, have become a threat to liberal America.

***

“He’s a huge deal. He’s the Godfather.” Eric Craig’s eyes light up when I ask him about Rawles. Eric is one of a number of specialist estate agents for fleeing Redoubters. Seven years ago, he was one of them: fed up with California’s liberal approach to drugs — “you could smell pot everywhere!” — he upped sticks to conservative Idaho. We meet at a coffee shop in Sandpoint, a former railroad town on Lake Pend Oreille.

Eric sits with his back to the wall, monitoring each customer as they come in — he’s ex-military. But for the most part, he wears his defence training lightly. One minute, he’s joking goofily with the kids behind the counter; the next, he’s explaining why military-grade bunkers are overrated (you’re a sitting duck).

For Eric, business really boomed after the 2020 election. “During the transition, between November and January, I sold more homes than I can count.” The main reason, he says, is because people were terrified that a Biden presidency could accelerate America’s downfall. Next summer, he’s expecting a wave of Redoubters to arrive for similar reasons. “What happens if Biden becomes President again? Or Kamala Harris? Many people think they’re going to try and steal the election. Will the US allow that to stand?”

His clients have bigger concerns, too. “The threats they cite are like a flavour of the month. Sometimes it’s a nuclear strike, or the Chinese invading, or government overreach.” He describes one customer who believes the poles are about to shift, causing tidal waves more than a thousand feet high. “So he bought a house on the top of a mountain,” Eric says, half-rolling his eyes.

For the most part, though, Redoubter ranches are more modest affairs. Drive a mile down the private roads that disappear into Idaho’s forests, past the “NO ENTRY” signs, and you’re more likely to find a homestead flanked by giant solar panels. There, in its 20 acres of land, you’ll spot an off-grid generator, a purpose-built well, a few animals and a vegetable garden; inside, you’ll find a storage room lined with tins and a giant freezer filled to the brim. Everything, from the curved driveway to the sightlines through the trees, is designed with security in mind. “It’s best to bury your propane tanks underground,” Eric advises, so that an intruder can’t shoot them.

Yet he is keen to make clear that extreme isolation isn’t an absolute priority. “Less than 5% of Redoubters just want to be left the hell alone. People like and need to develop a community of neighbours and friends who can help them, especially when times get tough.”

Two of those friends are Brian Welch and Patrick Devine, who have separate ranches a few miles away near Athol. Both lived in Los Angeles when it was crippled by looting during the Rodney King riotsin 1992. And both lived in the city when its social contract was fractured by a series of earthquakes in the same decade. Today, by contrast, the three of us are sitting outside a bar in Bayview, an empty village guarded by mountains on three sides and a lake on the other. The water doesn’t move, transfixed.

Brian, a devout Christian, describes himself as “a Redoubter before the Redoubt even started”, having escaped California with his family in 1993. He’s a God-fearing man whose life is centred on his ranch and family. “I’ve been married to the same woman for 40 years,” he says without me asking.

His journey to Idaho started in the high desert above Los Angeles. “I used to have to drive across the San Andreas fault line every day,” he says, describing his commute to work. “If another earthquake happened [as one did the following year], I could have been cut off from my family completely.” Los Angeles, he explains, was already a tinderbox. When the Rodney King riots erupted, Brian was caught in the city and surrounded by a gang of looters who only slunk off after he pulled out his gun. He put his house for sale and waited for a sign from God — it came six days later, when someone bought it straightaway.

Why does he think so many have joined him? Brian quotes Rawles: “There is a very thin veneer of civilisation’, and its edges are starting to peel off. You can feel it.” Even in the Redoubt? Yes, he says, before describing a recent incident in nearby Coeur D’Alene, when a car thief attempted to run over its 74-year-old owner. Then comes the twist: “The owner jumped on the bonnet and shot him dead through the windshield!”

This would seem to be the Redoubter way of dealing with crime: to take matters into your own hands. He goes on to describe the tense months after George Floyd’s death, when it was rumoured that busloads of Antifa activists were travelling to Coeur D’Alene to hold a Black Lives Matter protest. In response, groups of vigilantes armed with semi-automatic weapons patrolled the streets on successive evenings. “If you guys are thinking of coming to Coeur D’Alene, to riot or loot, you’d better think again,” said one of those involved. “Because we ain’t having it in our town.” The Antifa threat never materialised.

Patrick knows all about such threats. As a former emergency medical technician in LA, he’s seen it all: three earthquakes, one well-known riot, and the heyday of the city’s gang wars in the Nineties. “We’d walk into the middle of full-on shootouts,” he says casually. “We were always getting shot at…” A marriage, a financial crash and a few attempts to relocate later, he discovered Rawles’s work and decided to get out of Dodge. “I never want to be a victim,” he adds.

Instead, Patrick now teaches emergency first aid and firearms skills to fellow Redoubters. One of the tasks he sets them is to shoot a cardboard assailant standing behind a hostage with a loved one’s face stuck on it. “So far, nobody has missed.”

He also regularly meets friends to train them with their firearms and coordinate strategies in case their ranches are attacked. “There’s not much police around here,” he explains. “Perhaps two officers covering 50 square miles.” And, he adds, “they’re pretty relaxed if you need to shoot someone to defend yourself”.

It’s not all about guns. Patrick, like many Redoubters, has several dogs who can be “somewhat aggressive”. He clarifies: “If you’re dumb enough to walk into my house, it’s going to be an ugly moment in your life. You might not get out alive.”

***

James Wesley, Rawles wouldn’t let me walk anywhere near his house: he doesn’t trust the media. His only previous face-to-face interview was with a friend who worked for a now-defunct electronics magazine. Since then, “any time that mainstream American journalists interview me or write about the American Redoubt movement, they try to mischaracterise me and the movement as racist”. He sends me a link to a blog post that makes it “abundantly clear that I reject racism”.

Sitting across from me in a diner off Route 95 somewhere between Coeur D’Alene, Idaho, and the Canadian border, neither Rawles nor his wife Lily come across as far-Right Rambos: they have the air of geography teachers who have retired to their local church group. “Jim”, with a white wispy beard and a pair of hearing aids; and wide-eyed Lily, with a tanned, expressive face that dances gleefully from one eccentricity to another. She orders a burger patty; he drinks a glass of lemonade mixed with huckleberry syrup.

Rawles’s apocalyptic fears, he tells me, were born of a childhood spent in Livermore, California, home to the National Laboratory that designed atomic weapons during the Cold War. “I grew up in the shadow of the nuclear bomb,” he says. Unable to follow his father into the Air Force because of his poor eyesight, Rawles became a Military Intelligence Officer, where he served in Cold War Germany and saw “how fragile the world is, how close it is to systemic collapse”.

He arrived in Idaho in 1993 after resigning his commission on the day Clinton became President:“I didn’t like the idea of him as Commander-in-chief.” There he focused on writing his books and survivalist tips; it was his first, late wife, “the Memsahib”, who suggested in 2005 he start a blog.

And so his gospel was handed down via SurvivalBlog, the daily posts uninterrupted until one was published by the Memsahib in 2009. In it, she revealed she had two months to live and wanted to find “a new wife for my husband”, describing him as “extremely devoted”; “punctual and neat”; “a worrier”. She issued a checklist of qualifications: “Be a devout, church-going Christian”; “Willing to live at the Rawles Ranch”; “Willing to put up with Jim’s eccentricities”. Applicants were instructed to write in.

Of the six women who did, one was Lily, a widow and avid reader of the blog. Six months passed before Rawles replied. They spoke on the phone, hit it off, and Rawles travelled to meet her at her home “somewhere in New England”. Weeks later, they married and returned to Idaho with Lily’s daughters.

Ten years on, they run the ranch and the blog, breaking only for the Saturday Messianic Sabbath, when they attend a Bible study group. The whereabouts of their fastness — with its chickens, sheep, cows, horses and orchards — remains a closely guarded secret, to protect them when society eventually collapses and intruders seek them out. The only people they frequently meet belong to their Bible group or are neighbours with whom they semi-regularly trade produce: hay, meat and preserved goods. “Mostly we just want to be left alone by the Government,” says Lily. “We just want to take care of ourselves: to raise our families and enjoy them and be healthy.”

But the Redoubt isn’t just an idyll — it is also a militarised fortification to fall back on and defend. And it’s in discussing this that Rawles shows what the Memsahib called his “eccentricities”. When I ask about impending cataclysms, he describes how the microcircuits in all modern devices could be destroyed by an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) caused by a nuclear explosion in the earth’s atmosphere. It is a common fear among the Redoubters I meet; they invariably point to the nuclear capacity of Russia and China, as well as the US Government task forcededicated to preparing citizens for the inevitable EMP.

Rawles’s greatest concern, however, is economic collapse brought on by the size of America’s national debt — and the lawlessness that would follow. “My fear is that we’re just a few meals away from anarchy,” he says. “Inflation is massively underreported. People are not keeping up. Tent cities are appearing everywhere. I think that’s where we’re headed…”

And what of the Redoubt’s political and religious criteria? The flags and signs I saw on rural ranch paths — “Fuck Biden”; “Trump 2024: Fuck your feelings” — suggest it is little more than a sanctuary for disillusioned Christian nationalists, or a case of “Donald Trump voters building a new state”. Lily fiercely corrects me. While she voted for him in 2020, “Trump is now part of the whole system… Then there was the vaccine. He used to be against them, but now he’s not. He lied.” She looks away in disgust.

Rawles didn’t vote in the last election either; in fact, he hasn’t voted for 15 years “because of the privacy issues involved in registering”. He probably would have voted for Trump in 2020, but now doesn’t trust him. “I don’t like his associations and business connections.” “Epstein!” Lily clarifies. Neither will vote next year.

But many Redoubters clearly are embittered Trump supporters. Twenty miles up the road, a giant sign — “Welcome to Trump County” — watches over the highway, while Radio Free Redoubt dedicates its show on Tuesdays to praising America’s true “commander-in-chief”. And then there are those such as Matt Shea, who called for people to prepare for “total war” after the 2020 election was “stolen”.

“You can pick friends but not your family,” Rawles responds, not entirely convincingly. “I did worry about neo-Nazis when I started the movement… But the Redoubt is a philosophy, not a political party or a club. It is a form of leaderless resistance. All I did was wind up a toy and let it go…”

After lunch, Rawles suggests we drive into the mountains to see the amber-autumn splendour of Idaho’s tamarack trees up close. It’s another of his eccentricities; he giddily points them out as if they are magical creatures, his apocalyptic disquiet briefly forgotten.

But it’s impossible to shake it off completely: the oppressive sense of doom, and the pessimism that underscores his movement. On one level, the Redoubt appears to be little more than “political alienation with more forest and guns”. But its tragedy also runs deeper.

The idea of alienation carries the hope that one day the alienated will find a voice — that they are the product of circumstances that can be reversed. Rawles’s Redoubt, by contrast, seems an acceptance of defeat. After all, it is premised on the belief that America can’t be saved. That its people and their representatives are the cause, rather than the solution, to its very real crises. That the nation, along with its citizens, is Fallen.

When I raise this, Rawles is adamant. “God said we’re not of this world.” He pauses. “I’m not looking forward to things falling apart, but I’m ready for it when it happens.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.